BTN News: The film industry has long been captivated by historical figures whose lives teetered on the edge of madness and grandeur. Among these, few figures have been as controversial and enigmatic as Caligula, the Roman Emperor whose legacy is mired in tales of excess, cruelty, and unrestrained power. The 1979 film “Caligula,” originally conceived as a bold and ambitious project, sought to capture this complex character and the decadence of his reign. However, what was intended as a cinematic masterpiece devolved into a notorious spectacle of explicit content, disjointed storytelling, and creative disputes. Recently, a new version of this infamous film has emerged, breathing fresh life into a project that was almost lost to time. This restored version, known as “Caligula: The Ultimate Cut,” offers a radically different perspective, one that aligns more closely with the original vision of its creators and promises a deeper exploration of the themes of power, corruption, and moral decay that define Caligula’s story.

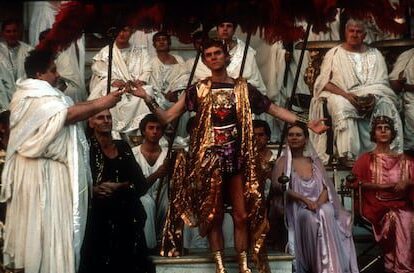

The film begins with a prologue set in Rome in the year 37 AD, where we find Caligula, portrayed by Malcolm McDowell, awakening next to his younger sister, Drusilla, played by Teresa Ann Savoy. This opening scene, previously unseen until its recent restoration, immediately establishes the complex and disturbing relationship between the siblings, hinting at the blend of love, fear, and madness that will characterize Caligula’s rule. McDowell’s portrayal of Caligula is both nuanced and unsettling, showcasing a man who is as vulnerable and childlike as he is terrifyingly unpredictable. His bond with Drusilla is presented not just as incestuous, but as a foundation for his fragile mental state, underscored by dreams of his grandfather Tiberius, played by Peter O’Toole, plotting his demise.

This scene, like much of “Caligula: The Ultimate Cut,” was originally filmed by the Italian director Tinto Brass in the spring of 1976. However, due to various production and creative conflicts, it remained unseen until recently, when it was painstakingly restored and recontextualized by film historian Thomas Negovan. Negovan’s work on this project involved sifting through over 97 hours of original footage, much of it languishing in the archives of Penthouse magazine, the film’s controversial backer. His goal was to reconstruct a version of “Caligula” that was not just coherent but also true to the ambitious vision that the film’s original creators had in mind—a vision that was dramatically altered by the film’s producer, Bob Guccione, founder of Penthouse, who infamously inserted explicit sexual content in a bid to make the film more commercially viable.

What emerges in “Caligula: The Ultimate Cut” is a film that feels more like the political thriller and dark satire it was meant to be, rather than the chaotic and grotesque spectacle that audiences originally encountered. The film has long been remembered as a series of cruel and grotesque orgies, set against a backdrop of cardboard-thin sets, its narrative barely holding together under the weight of its own excesses. Yet, in this restored version, a clearer story begins to take shape—one that reflects on the corrupting influence of absolute power, the fragility of the human psyche, and the dark allure of unbridled authority.

Malcolm McDowell, whose performance has often been dismissed along with the film itself, has long insisted that “Caligula” was one of his best roles. His enthusiasm for the restoration project is understandable; finally, audiences can see the depth of his portrayal—a man driven mad by power, yet still clinging to a twisted form of humanity. Helen Mirren, another of the film’s stars, famously described “Caligula” as a perfect blend of “art and genitals.” While this description may have been tongue-in-cheek, it reflects the film’s original ambition to combine high art with unabashed sensuality, a combination that was lost in the original release but is now, at least partially, restored.

Negovan’s restoration work has been nothing short of a cinematic resurrection. It took nearly three years of meticulous effort, but the results are already being recognized. Where the original release of “Caligula” has languished with a dismal 21% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, “Caligula: The Ultimate Cut” boasts an impressive 86%. This dramatic turnaround reflects the film’s transformation from a historical curiosity into a piece of cinema that can finally be appreciated for its narrative depth, artistic ambition, and the performances of its cast.

The original “Caligula” was one of the most controversial films of its time, with its release sparking outrage and condemnation from critics and audiences alike. Bob Guccione, in his quest to make the film the pinnacle of erotic cinema, overruled the creative team, including director Tinto Brass and screenwriter Gore Vidal, who had vastly different visions for the project. Vidal, who had penned an initial 400-page script, envisioned a story that was as much about the moral decay of the Roman Empire as it was about the personal downfall of its most infamous emperor. However, Guccione’s desire to cater to his Penthouse audience led to the insertion of explicit scenes that Brass and Vidal vehemently opposed, ultimately leading to Brass disowning the film and Vidal distancing himself from it entirely.

The conflict between Brass and Vidal was rooted in their differing interpretations of Caligula himself. Vidal saw Caligula as a fundamentally good man driven to madness by the corrupting influence of power and the paranoid environment created by his grandfather, Tiberius. Brass, on the other hand, envisioned Caligula as a sociopathic tyrant, whose sadistic tendencies were merely waiting for an opportunity to surface. This creative rift led to a near-complete rewrite of Vidal’s script by Brass, with Guccione’s approval, turning what was supposed to be a politically charged drama into something far more explicit and controversial.

The film’s troubled production didn’t end with creative disputes. When it finally premiered, it did so without the signature of its director, with its original script butchered and its cast disillusioned. Critics lambasted the film, with some describing it as a “cinematic abomination” and a “moral holocaust.” The harshest criticism came from Roger Ebert, who called it a “depraved and unrelenting” piece of pornography that was nearly three hours long. Yet, despite the critical mauling, “Caligula” managed to carve out a place in popular culture, largely because of its notoriety and the controversy surrounding its release.

Over the years, “Caligula” has maintained a presence in the cultural zeitgeist, often as a symbol of the excesses of both ancient Rome and 1970s cinema. Its legacy is one of infamy, a film that was reviled publicly but consumed privately, giving rise to a peculiar form of cult status. This status was further cemented by its influence on the peplum genre—a subgenre of films that combined the swords-and-sandals aesthetic with explicit eroticism. Though the genre has largely fallen out of favor, its roots in “Caligula” are undeniable.

The new cut of “Caligula” doesn’t just offer a more coherent narrative; it also challenges the deeply ingrained perception of the emperor as a one-dimensional monster. The character of Caligula, as portrayed by McDowell in this restored version, is more complex, a man whose sadism and madness are portrayed as the tragic result of his environment and upbringing. This version aligns more closely with modern historical interpretations, which suggest that while Caligula was undoubtedly tyrannical, the stories of his more outlandish behaviors may have been exaggerated by his political enemies.

Yet, even with this more nuanced portrayal, the film does not shy away from the brutal realities of Caligula’s reign. The excess, the cruelty, and the descent into madness are all still there, but they are presented within a context that makes them more understandable, if not entirely forgivable. This approach not only humanizes Caligula to a degree but also makes the film a more effective political satire—a reflection on how absolute power can corrupt absolutely.

With the release of “Caligula: The Ultimate Cut,” the film industry has been given a rare opportunity to revisit and re-evaluate a work that was once considered a failed experiment in cinematic excess. The new version allows us to see what might have been had the film not been subjected to the whims of its producer. It also serves as a reminder of the complexities of filmmaking, where creative vision can be so easily overshadowed by commercial interests.

The restored version of “Caligula” has closed a chapter that began nearly half a century ago, offering a resolution to a project that was nearly lost to time. As this version continues to gain recognition, it’s clear that the effort to restore the film has paid off, not just in terms of critical reception, but in giving audiences a chance to see a different side of this notorious piece of cinema history. For those who have only known the original, this new version is a revelation—an opportunity to see “Caligula” not just as a spectacle of debauchery, but as a film with something meaningful to say about the nature of power, the fragility of the human mind, and the dark allure of absolute authority.